Publisher:

Publisher: Cambridge University Press (2006)

Details: 345 pages, Hardcover

Price: $80.00

ISBN: 0521852242

Category: Monograph

Topics: Mathematical Physics, Dynamical Systems, Classical Mechanics, Celestial Mechanics

MAA Review

[Reviewed by David Mazel, on 12/20/2006]

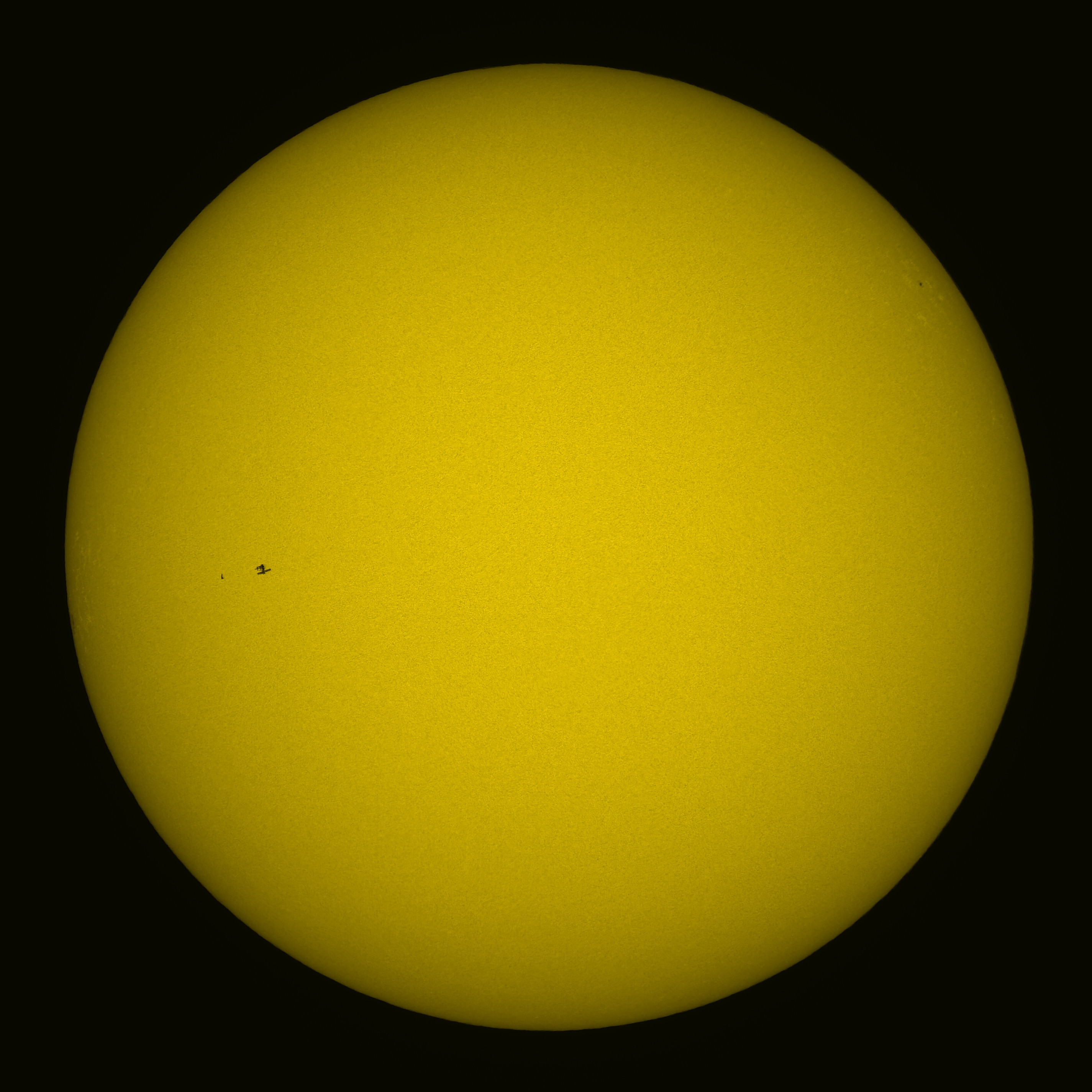

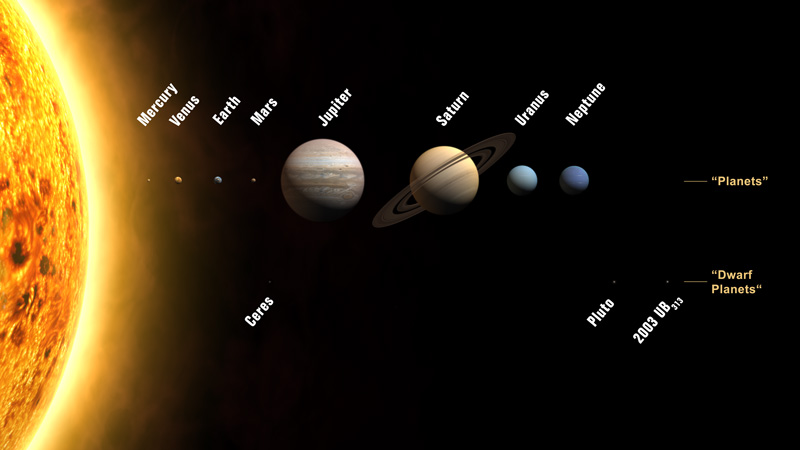

An undergraduate, having taken calculus and some physics, comes across the two-body problem. Specifically, what is the motion of two bodies in space acting under their mutual gravitational attraction? She quickly finds that she can solve the equations, and for given initial conditions, the solutions are conic sections. Then, the natural question to ask is: What is the solution if we now expand the system to three bodies? Here the problem is not so easy. In fact, it is impossible to solve in closed form.

This book begins by recounting what the student would have learned in that physics class and then goes into specifics of the three-body problem. Not only is the problem unsolvable in closed form; the solution, in general, involves chaotic dynamics. Nonetheless, there is much that can be learned by studying various forms of the problem under differing conditions. This book goes a long way to exploring these forms and explaining how the different scenarios can be approached.

The authors begin with a presentation of Newtonian mechanics and the solution of the two-body problem. The authors use physics to motivate the mathematics and derive the equations of motion — here, and throughout the book. Thus, the discussions are complete and present the ideas from the view of mathematical physics.

After discussion of the two-body problem we are introduced to Hamiltonian mechanics and some restricted three-body problems such as satellite orbits, and scatterings of bodies from a binary orbit. Other topics include escapes, three body scattering, and capture. The final topics deal with perturbations and various astrophysical problems such as black holes and the evolution of comet orbits.

Throughout the book the authors present diagrams to illustrate their points but these diagrams are limited in their utility. The authors could have presented more illustrative diagrams and figures to better qualify the text.

When I started reading I thought the book would discuss chaos and its relationship to the three body problem. After all, that's the first thought that comes to mind today. There is mention of this phenomenon, but very little, and no attention given to simulating orbits of three-body motion. For me, this was a disappointment.

Finally, the spirit of the book is mathematical physics; consequently, the authors often leave it to the reader to sort through the mathematics. I often found, for example, that I had to review earlier parts of the text and search for the equations — always present somewhere in the text but not explicitly noted nor cited — needed to follow the derivations and fill in many of the steps.

In short, this is a good text on the mathematical physics of the problem for the experienced practitioner. Everyone else, I'm afraid, will find it a challenge to read and follow the mathematics.

Publisher: Cambridge University Press (2006)

Publisher: Cambridge University Press (2006)